How This Book Came to Be

The seeds of this book were planted nearly a decade ago. We met in 2012 at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, where Jamie was an undergraduate student and where Adam worked as Director of Student Ministry at Duke Chapel. We watched along with thousands of others as the deaths of Trayvon Martin in 2012, Michael Brown in 2014, and Sandra Bland in 2015 sparked the #BlackLivesMatter movement in the U.S. and protests for racial justice around the world. We wondered how these global events would change us.

Police violence also erupted on our campus and in our city. Campus police used pepper spray and violent force against a man suspected of stealing a backpack on campus in 2014, and in 2016 Durham police shot and killed Frank Nathaniel Clark, claiming that he “made a sudden movement toward his waistband” during a conversation. Again in early 2017 Durham police killed two men in separate incidents, Kenneth Lee Bailey and Willard Eugene Scott, Jr. We wondered how these local events would change us, too.

We began to read Baldwin, together.

I (Adam) read as someone who is white. I navigate a world that is more or less built for me. The university where I work was founded to serve white southern men, like me. My gender identity resembles that of 46 U.S. Presidents, and my racial identity resembles that of 45. If I lost a few pounds I would be nearly the exact height and weight of the crash test dummies used in vehicle safety research since the 1970s.

Baldwin writes to overturn the racial order of this world, which requires a reckoning with my sense of self, history, and ethics. Baldwin is describing me when he writes, “The American white has got to accept the fact that what he thinks he is, he is not.”

I (Jamie) read as someone who is Black. I navigate a world that is more or less built for Adam. I am queer, and although I prefer not to identify along the gender binary, I was assigned female at birth and am often perceived and treated as a woman.

Baldwin writes to call marginalized people into full humanity and power. He echoes my experience when he writes, “It took many years of vomiting up all the filth I’d been taught about myself, and half-believed, before I was able to walk on the earth as though I had a right to be here”– but also my aspirations when he writes, “The point is to get your work done, and your work is to change the world.”

We also read as members of a multiracial community - in the narrow sense of our friendship, as well as in more expansive senses. We went to Duke - we’re both Blue Devils. We are from Charlotte, North Carolina (born 15 years apart) - we both know that the traffic on Providence Road is a nightmare. Baldwin writes to us not simply as a Black woman and a white man, but in this collective way, also. He is describing us when he writes, “If we are going to build a multiracial society, which is our only hope, then one has got to accept that I have learned a lot from you, and a lot of it is bitter, but you have a lot to learn from me, and a lot of that will be bitter. That bitterness is our only hope. That is the only way we get past it.“

We began to write with Baldwin, together.

As the years passed, our reading turned into writing. Jamie started as a poet, and Adam started as a preacher, so we met in the middle and wrote prayers.

Give us new voices

like Baldwin’s

to call for revolution.

Give us new hearts

like Baldwin’s

to love with holy passion.

Give us new spirits

like Baldwin’s

to pray without ceasing. Amen.

We wrote prayers full of grief, prayers full of anger, and prayers full of gratitude. In almost every case we anchored our prayers to the memory of someone killed by police - Tamir Rice, Mya Hall, Natasha McKenna, Philando Castille … the list is so, so long.

Sometimes we found that we couldn’t write the words together, so we split columns on the page, each using our unique voice. Other times we found that the prayers required something more than words, so we added descriptions of local community programs protesting police violence or web links to national organizations fighting for racial justice.

We decided to share our prayers with others. We commissioned Lindsey Bailey, an illustrator in Memphis, TN and Janna Morton, an illustrator in Baltimore, MD to create images of Baldwin, and we bought a website. In August 2017 we began releasing one prayer each day for 30 days. We called it Praying with James Baldwin in an Age of #BlackLivesMatter. The project remains online - you can still find it here at www.prayingwithjamesbaldwin.com.

Then, as happens, things changed. Adam took a new job outside of the church. Jamie moved to Kenya and began writing her first novel. We thought we were done with Baldwin.

Then, as happens, things stayed the same. In spring 2020 racial justice protests erupted across the U.S. as millions of people decried the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, MN and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, KY. In our grief and anger, we started reading again. Baldwin was not done with us.

We had to begin again with Baldwin, together.

Writing with Baldwin was different this time. We wanted to revisit some of the incredible scenes in his novels and short stories that we missed the first time around. We wanted to challenge some of the ways he fell short and resist the desire to treat him as a perfect witness. We wanted to capture some of the indelible moments in his life.

Most of all, we wanted to capture the intensity of his moral demand.

The form and function of our writing changed. Prayers didn’t feel quite right, anymore. Rather than writing to God, we focused on writing to you.

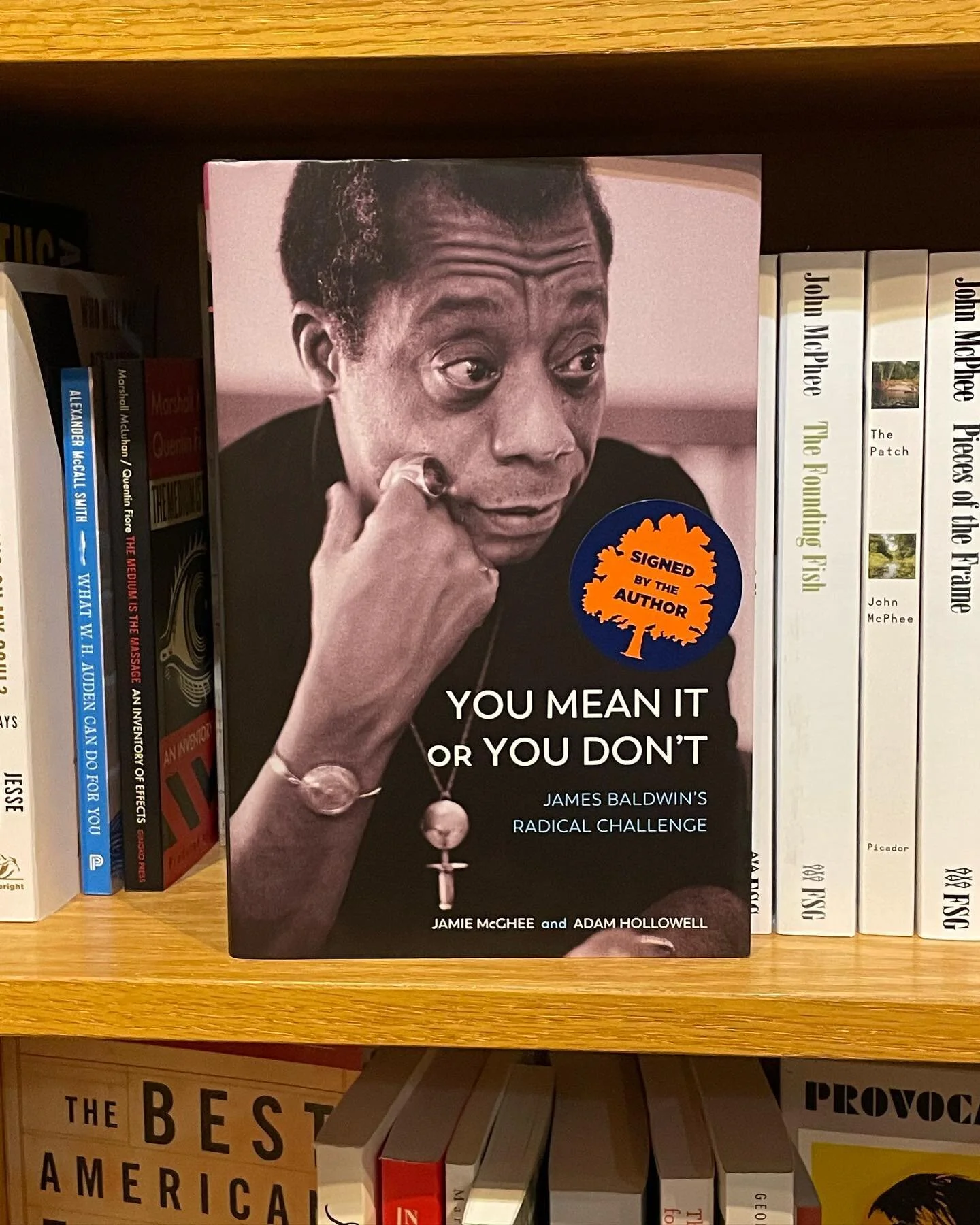

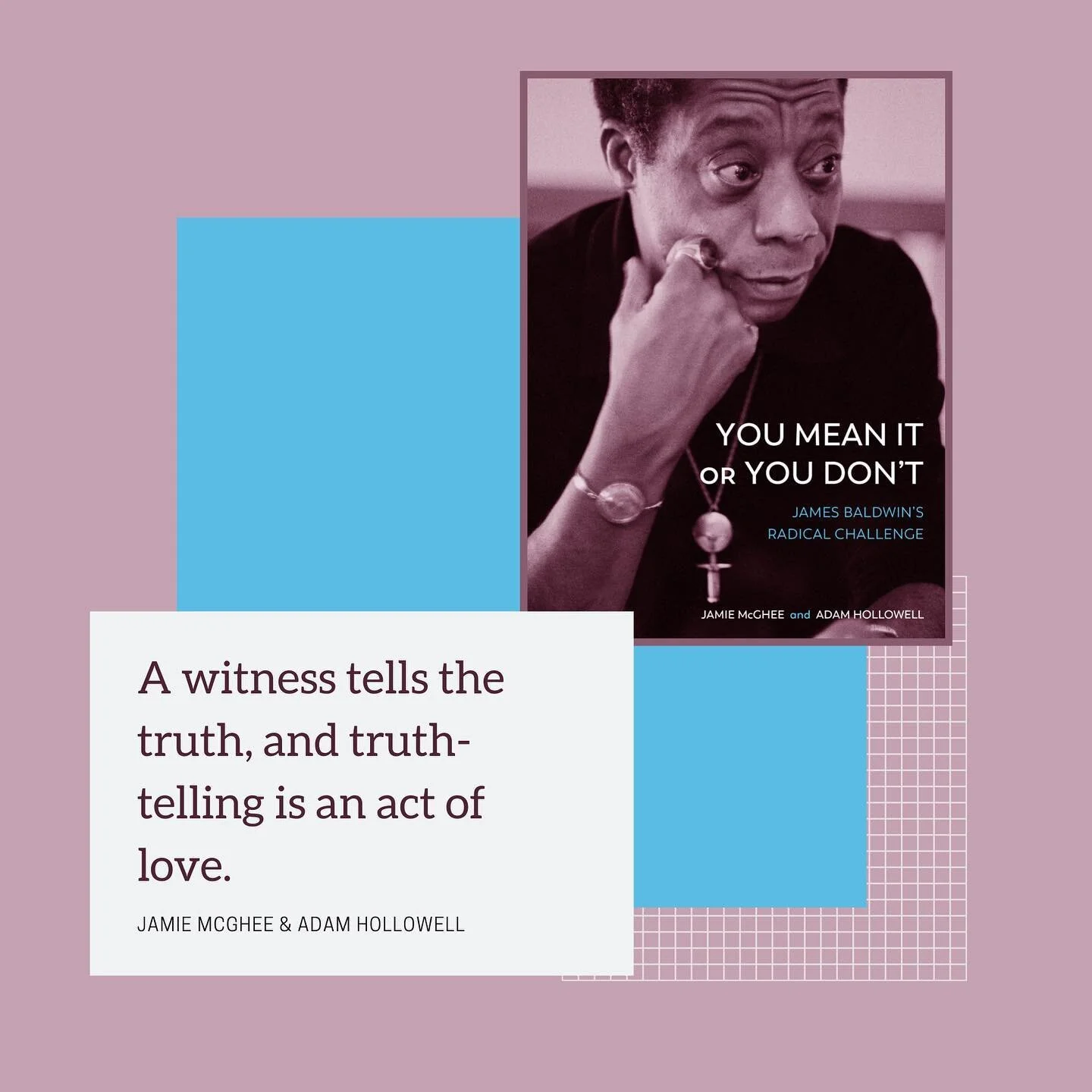

The title, You Mean It Or You Don’t, is for you. It is for us, too. It is an invitation into Baldwin’s demand for responsibility, honesty, and accountability in a time of great moral evasion. It is not a threat but a statement of fact. It should excite and unnerve us at the same time.

We also want to help you move from conviction to action. Throughout each chapter you will find prompts with concrete steps to work for justice in your homes, neighborhoods, schools, communities, churches and other religious groups. The sections are labeled “Act,” and they include information about national activist organizations, websites to register for training and service programs, and online resources to learn from and share.

“To act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger,” Baldwin wrote in The Fire Next Time. In our decade of reading Baldwin together, what we have written in here is the most dangerous of all our writing. It is dangerous in precisely the way Baldwin intended - the kind of danger born of action with purpose in a world of apathy.

About Us

Jamie McGhee

Jamie McGhee is a novelist, playwright, and essayist. For her fiction, she was named a James Baldwin Fellow in Saint-Paul de Vence, France, and a Sacatar Fellow in Itaparica, Brazil. She has also been awarded artist residencies at Blue Mountain Center in New York, Zentrum für Kunst Urbanistik in Germany, and Sa Taronja Associació Cultural in Spain. With ties to the eastern US, she is now based in Berlin, Germany.

Adam Hollowell

Adam Hollowell is an author, ethicist, and facilitator whose work addresses social inequality and promotes collective efforts for a more just world. His writing has been published by Broadleaf Books, Duke University Press, Eerdmans, Men & Masculinities, Inside Higher Ed, and the Journal of American College Health, among others. He is a recipient of research and study grants from the Brady Education Foundation, the Franklin Humanities Institute, the Scottish Funding Council, and the Duke Endowment. He delivers keynotes, lectures, and creative workshops across the country.

An award-winning educator, he teaches ethics and inequality studies across multiple departments at Duke University, including the Kenan Institute for Ethics, the Program in Education, the Department of History, and the Sanford School of Public Policy. He serves as Senior Research Associate and director of the Global Inequality Research Initiative at the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity, where he is also director of the Inequality Studies minor and faculty director of the Benjamin N. Duke Scholarship. He lives in Durham, North Carolina.